Personal Research and Articles

Here, I have undertaken multiple personal research projects based on my interests. While these initiatives are just for my own skill enhancement, they reflect my commitment to continuously improving my data analysis capabilities. Through these projects, I looked into various datasets, exploring patterns and extracting actionable insights.

This portfolio showcases my journey, illustrating not only my technical skills but also my curiosity and dedication to leveraging data in meaningful ways. Happy reading!

Singapore’s Public Housing Affordability

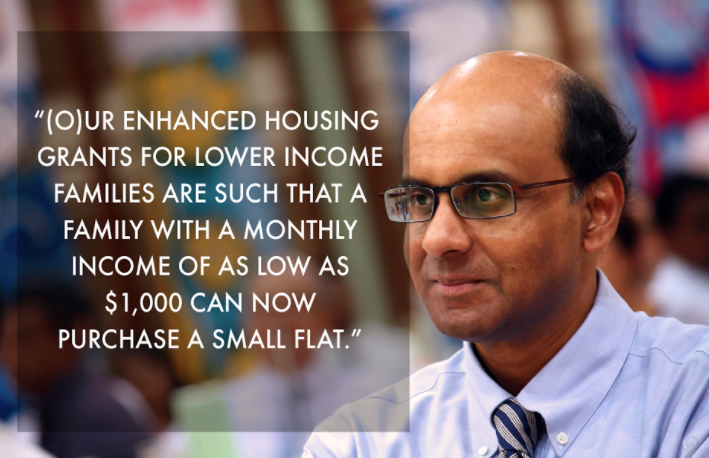

In Singapore, housing affordability has become an increasing concern for future Singaporeans. However, in 2012, then-Deputy Prime Minister (DPM) Tharman Shanmugaratnam stated that a household income of SGD $1,000 was sufficient to own a home, sparking discussions among netizens online (Tan, 2012). Read more here…

Is Public Housing Affordable for Singaporeans?

Monday, 6 Nov 2023

Investigating Singapore’s Resale Flat Prices from 1990 to 2022

While Mr. Tharman argued that housing grants could provide support for low-income households, many Singaporeans expressed concerns about the long-term viability of such claims, especially in the face of the constantly rising cost of living and property prices.

This brings up a big question—will public housing in Singapore really stay affordable for the average Singaporean in the future? In this post, we'll take a closer look at how the housing market is evolving and what it could mean for future generations trying to own a home.

We’ll dive into the complexities of the housing market, analyze potential long-term trends, and explore how factors like estate, size, and remaining lease impact affordability. Ultimately, this analysis aims to identify the key factors that matter most.

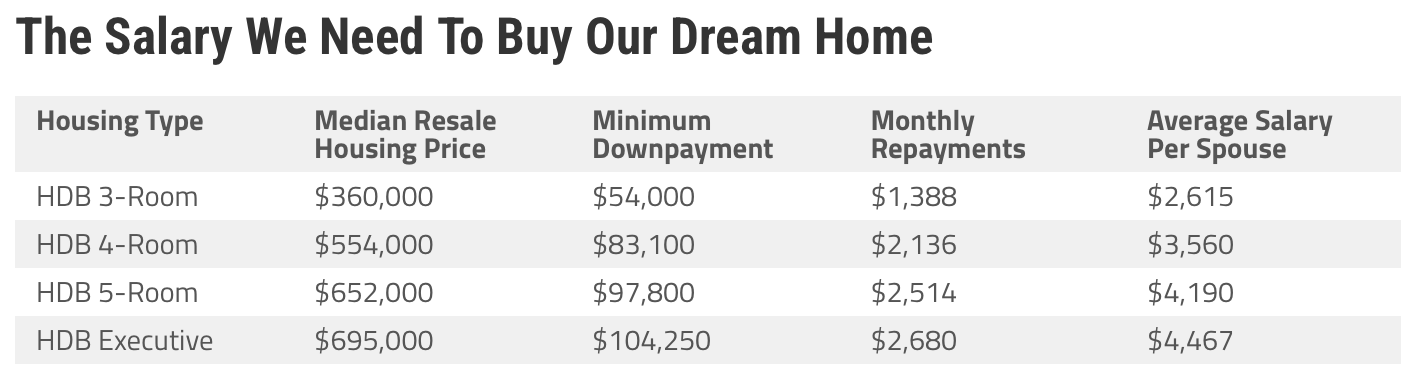

According to Kumar (2022), housing affordability in Singapore is a complex issue with many moving parts. The table above outlines current housing prices, offering a useful guide to understanding the financial commitment involved. Based on this data, it estimates the average salary each spouse would need to comfortably manage monthly repayments.

For example, to afford a 3-room flat with a median price of $360,000, both partners would need to earn at least SGD $5,230 each. While this may seem manageable at first glance, it doesn't take into account other living expenses or potential income fluctuations. Couples may have additional financial commitments, such as owning a car or raising multiple children, which can significantly impact their overall affordability.

magine you and your spouse are planning to start a family. Now that we've taken a glimpse into the affordability of homes in Singapore, do you think you'll be able to comfortably own your own home when the time comes? Let's dive into the real data and explore this critical issue further.

Trend of HDB Resale Prices in Singapore

To understand the trend of housing prices in Singapore, the analysis will use the available data sets from this site. The publicly available data contains historical sales figures on yearly bases, and can be used to access market dynamics and predict future trend.

Before diving deeper into the analysis, let’s first take a look at how housing prices have increased from 1990 to 2022. While the general upward trend in prices aligns with Singapore’s economic growth, the rapid surge over this period is quite alarming.

Some might argue that the rising prices are a reflection of a thriving economy. However, on the flip side, they also raise serious concerns about overall affordability. Now, let’s take a closer look at the graph below to better understand the trends:

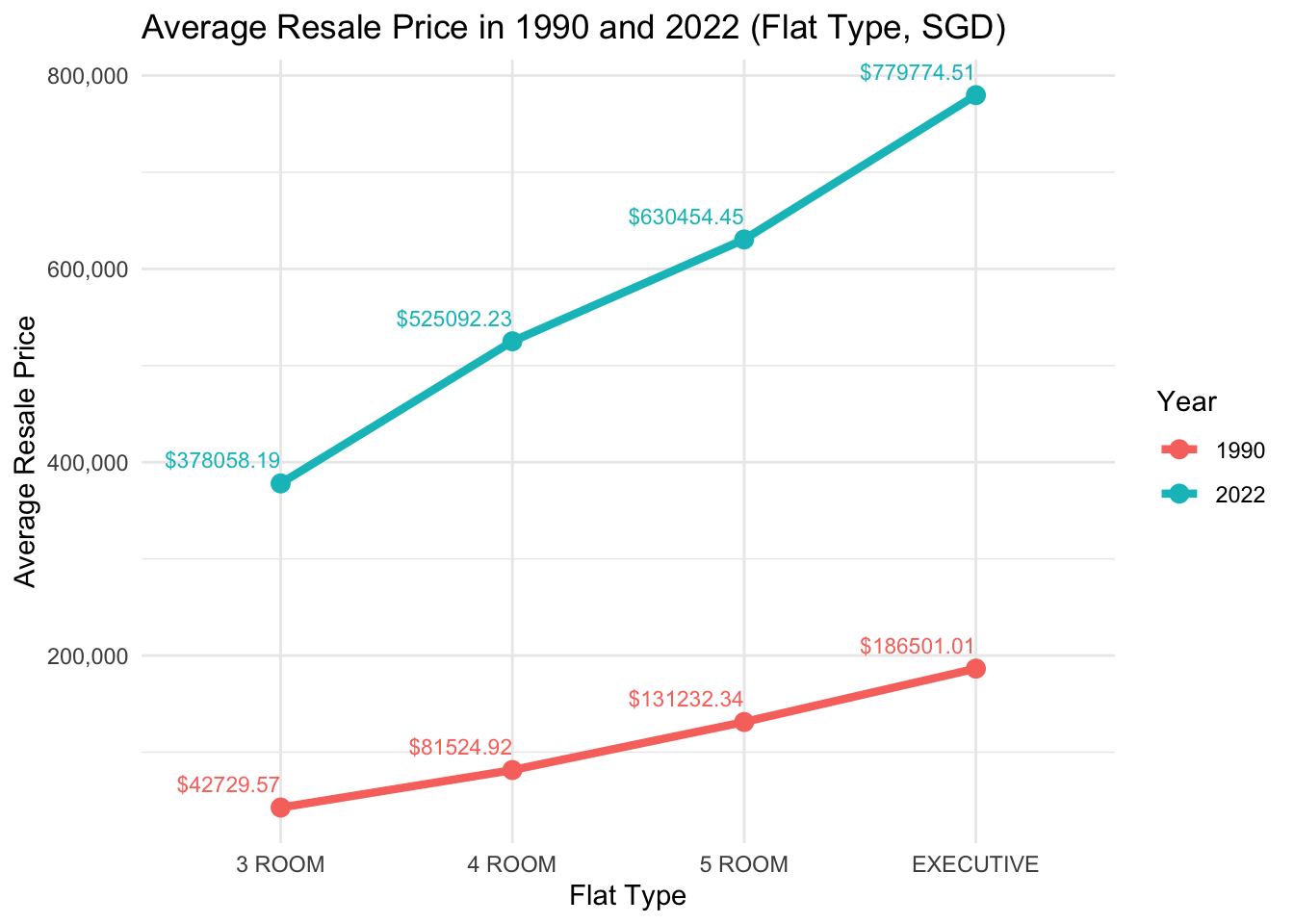

The graph above shows a significant steepening in the trend of average resale prices in Singapore from 1990 to 2022, highlighting the sharp rise in housing costs across all flat types. The steeper slope in 2022 reflects a more pronounced price escalation compared to the 1990s. This trend could indicate growing pressure on affordability and an increasing financial strain for prospective homeowners.

Notice on the graph that there's a concerning widening price gap between each successive flat type, with the difference in average prices becoming more pronounced over time. The jump in prices from a 3-room to a 4-room flat, both in 1990 and 2022, suggests a growing demand for larger homes. After all, a bigger home often means plans for a bigger family, right?

With that in mind, the widening price gap could pose a significant financial burden for upgraders seeking more spacious accommodations for a growing family. This increasing disparity highlights the importance of careful planning when it comes to home ownership to avoid potential buyer’s remorse in the future.

Comparing Average Resale Prices of Flat Types by Years

Now, let's take a closer look at the price increases for each flat type individually across both years. The graph highlights a significant difference in the cost of a 4-room flat between 1990 and 2022. This stark contrast underscores how much prices have surged over the years, emphasizing the growing challenge of affordability for aspiring homeowners.

In 1990, the average price of a 4-room flat was SGD $81,525, while in 2022, it skyrocketed to SGD $525,092—represented by green and orange markers on the graph, respectively. Check out the graph below to explore and compare the prices of other flat types between 1990 and 2022!

As mentioned earlier, the rising trend in housing costs, as shown in the graph, suggests that potential homeowners may face significant financial barriers when searching for suitable housing options. Furthermore, the data indicates that the real estate market has become increasingly segmented over time. Unfortunately, with growing demand and limited supply, property agents are capitalizing on the eagerness of potential homebuyers (Lam, 2020).

For instance, in 2019, a property agent was found guilty of engaging in unethical bidding practices to secure a higher commission (Lim, 2019). To address such issues, regulatory bodies must implement and enforce strict rules and guidelines to promote fair practices in this highly competitive and high-stakes market.

The Distribution of Resale Flat Prices of Different Flat Types

While rising prices can signal affordability concerns, it's important to assess if they remain within a “safe” median range. However, the box plot below shows outliers that highlight significant and unprecedented price surges, raising concerns about long-term affordability.

Hint: Pay attention to how 3-room flats almost hitting $1,000,000! On top of that, we can also visually compare the number of outliers in 1990 and 2022, denoted by the green and orange box respectively.

Let’s input all the flat type options, what do you see? With 3-Room, 4-Room, 5-Room and Executive selected, we can see a consistent pattern. The data reveals a distinct trend where “regular-sized” flats are slowly approaching the million-dollar mark in resale price in 2022.

The upward trajectory is also an indication of the growth in the resale market, reflecting how people are willing to pay for their dream home. This inevitably affect those within a lower income bracket, preventing them to do the same.

Furthermore, across other flat types, the increasing number of outliers beyond the upper whiskers of the 2022 box plots suggests substantial market growth. However, it also indicates a rising number of exceptional cases where resale prices are commanding even higher premiums—far exceeding already high median trends.

Now that we’ve seen the high prices Singaporeans are willing to pay for their dream home, what other factors could be driving these increases? Next, we’ll explore whether factors such as the remaining lease or the flat’s location play a significant role in resale prices.

The Impact of Remaining Lease on Resale Prices

To ease the financial burden, some flat upgraders may consider purchasing a flat with a shorter remaining lease. But does the remaining lease actually correlate with the resale flat prices in 1990 and 2022? Let’s take a closer look at whether this factor influences affordability over time.

As we dive into the numbers, it's clear that patterns have shifted significantly from 1990 to 2022. In this section, we'll compare data from these two distinct years to uncover key trends. Now, take a look at the scatterplot below—pay close attention to the red line. What does it reveal about the relationship between remaining lease and resale prices?

In 1990, the trend was clear—a longer remaining lease often meant a higher resale price. The upward slope of the regression line was quite steep, indicating that buyers valued flats with longer leases, as they provided long-term security without lease expiration concerns.

In 2022, while there’s still a correlation, the slope is less steep, suggesting that the remaining lease is no longer as strong an indicator as it was in 1990. The data points are more spread out, showing greater variance in resale prices. This indicates that factors like location, flat type, and amenities have become more important than lease length in determining a flat’s value.

Put yourself in the buyer’s shoes—would you prefer a flat with a longer remaining lease but located an hour away from everything, or a shorter lease with all the conveniences just a stone’s throw away?

The answer isn’t just about counting the years left on a lease. So far, no HDB flat has reached the end of its lease, leaving uncertainty about what truly happens next. Buying a home is also about balancing the value of time and quality of life. After all, what’s the point of a long lease if it comes at the expense of convenience and daily comfort? Now, let’s dive into another crucial factor: the estate.

The Influence of Estate on Resale Prices

Price is undoubtedly a major factor when purchasing a home, but have you decided where to live? Would you prefer to stay close to your parents in the same estate, or do you have a specific school in mind for your future children? Next, we’ll explore how the estate impacts resale flat prices and identify which areas tend to be more expensive or budget-friendly for settling down.

Now, let’s explore the violin plot on the interactive dashboard, focusing on Bukit Timah and Punggol. According to 99.co (n.d), Bukit Timah is popular for its proximity to top schools like Hwa Chong Institution, National Junior College, and Raffles Girls’ Primary School, making it a highly sought-after estate

Punggol, on the other hand, is a relatively new estate that's gaining popularity among younger couples. With modern amenities and promising development plans, it's being designed as an eco-friendly and sustainable town, offering trendy lifestyle hubs that cater to all age groups.

With that in mind, let’s analyze the violin plot. We can observe a wider distribution of resale prices, with a more pronounced upper tail. This suggests a greater variety of flats available, while also highlighting a substantial market for high-end luxury units.

On the flip side, Punggol shows a narrower but denser concentration of prices, indicating less variation in resale prices. Now, go ahead and interact with the plot—select your dream estates and explore the price differences! And just in case, I’ve included the MRT map here for easy reference!

Ultimately, deciding the best place to settle down depends on what matters most to you. If you prioritize tranquility and scenic sea views, Punggol might be the perfect fit.

However, if being close to prestigious schools is your priority (yes, all schools are good schools—but let’s not get into that), then Bukit Timah might be the better choice. These visualizations not only reveal price trends but also reflect lifestyle preferences and your long-term family vision.

Conclusion: Why such analysis is important?

Year after year, resale HDB prices have continued to rise, reflecting the growing demand for housing in Singapore. However, this trend raises concerns for many Singaporeans, especially younger couples looking to start a family, as they face increasing challenges with affordability and availability.

Recent reports indicate that analysts expect resale flat prices to rise moderately for the rest of 2023 (CNA, 2023). While cooling measures have been implemented to control prices, the growth observed in the third quarter of 2023 was driven by price resistance amid inflation and affordability concerns.

You might be thinking: Build-to-Order (BTO) flats are actually that much cheaper? And you’re absolutely right! But are you ready to compete with tens of thousands of couples, wait 5-6 years, and still risk not getting a flat? Choosing to ballot for a BTO, despite its lower cost and grants, comes with its fair share of uncertainties and risks.

This analysis offers a thoughtful evaluation of the need for immediate housing versus the potential delays and challenges of the BTO process. For now, the best approach is to make the most of available grants and focus on purchasing within our means.

Educational Deviance in Singapore: A Case Study of Truancy and Societal Reaction

This study examines the impact of labeling on student identity within Singapore’s educational system through the case of “Jeremy,” a student labeled as a “truant.” Utilizing a life history interview, the research illustrates how societal reactions and the Compulsory Education Act of 2000 influence behaviors from primary to secondary deviance. Read more here…

Who Determines Deviant Behaviour?

Friday, 10 May 2024

Photo Source: CNA

The findings emphasize the detrimental effects of punitive measures and highlight the need for supportive reintegration strategies. This case underscores the broader implications for educational policy and practices in managing deviance constructively.

Background

In the heart of Singapore’s rigorous educational landscape, shaped by the Compulsory Education Act of 2000, every child is promised a solid 10-year foundational education. But beneath these statistics lies the personal struggle of students like Jeremy, whose life challenges disrupt the ideal path set before them.

The Story of Jeremy

“School was my second home until it wasn’t,” Jeremy recalls, his journey from a model student to a labeled ‘truant’ marked by circumstances beyond his control. When his father fell ill, the burden of financial support fell on his shoulders, forcing him to balance part-time jobs with his studies. This new responsibility led to tardiness and eventually, absences, which didn’t go unnoticed. “I wasn’t just late; I was struggling to keep my life together,” Jeremy shares.

Introduction

The Compulsory Education Act of 2000 (Singapore Statues Online, 2024) is a legal framework that ensures every child born after 1996 receives fundamental 10-year educational experiences, helping to develop a strong foundation in literacy, communication skills, and other moral values (MOE, 2023).

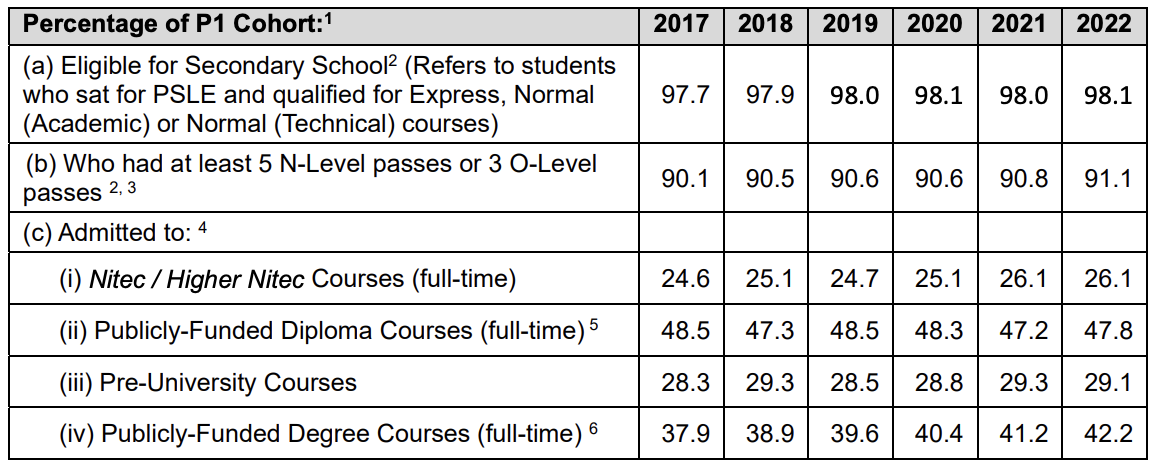

In 2022, the Ministry of Education’s (MOE) Education Statistic Digest reported that 235,116 children were enrolled on a Primary School and more than 98% of the Primary Six cohort were eligible for Secondary School education. Therefore, missing classes or being truant not only goes against societal rules but is also considered “deviant”, leading to social and legal repercussions.

Employing a life history interview approach, this essay explores how labelling influences “Jeremy” – a pseudonym – finds himself consistently confronted with the repercussions of being labelled as a “truant”. Therefore, using truancy and the Education Act as a backdrop, the article will discuss the impacts of societal responses on shaping Jeremy’s identity and also explore his initial behaviours, the impact of the punishments and the motivations that influenced his persistence in truancy during his time in a local secondary school.

Methodology

An hour-long interview was conducted face-to-face in his university hall residence. Having known Jeremy - the interviewee - for five years, his willingness to participate facilitated an open discussion. This allowed him to be honest in sharing his responses, thereby creating a more comprehensive interview. The interview hopes to address his experiences and societal influences that perpetuate his role as a “truant” within Singapore’s educational system.

Initial Challenges

Jeremy’s journey into truancy began subtly, with his behaviours initially deemed to be minor acts. During his time in secondary school, Jeremy had decent grades, great co-curriculum activities (CCA) records, and well-liked by everyone.

However, his life took an unexpected turn when his father fell ill. His mother had to reduce her working hours to care for his father. Being middle class, Jeremy started to pick up part-time jobs to financially support the family. The additional burden started to affect his well-being, physically and mentally resulting in him being late for school – a deviant behaviour according to Asiyai (2019).

Escalation to Secondary Deviance

His exhaustion began to manifest, and his tardiness became frequent and got the attention of his friends and teachers. When inquired about his late coming, his teacher said he “should be responsible for his actions”, which stood out. He retaliated and had to serve detention hours during and after class.

The detentions given by the discipline master were originally intended for corrective measures. According to Salovitta (2017), school detentions are widely used as a method of punishment. However, such practices can alienate, seclude and deprive the student of classes and interactions with their friends. Soon, detentions became a routine, inadvertently becoming a part of his secondary school life as he started to miss a full day of classes.

The Label Begins

During the interview, Jeremy mentioned a term used by this school to describe his offence. “Truancy & Repeated Latecomer Offender”. Furthermore, the detentions exposed him to other students who were deviant actors, reinforcing his behaviours and validating his identity within this marginalised group.

While undergoing his punishment, he began to internalise the label “truant”, given by his discipline master, which influenced his self-perception and behaviours. This would indicate that the measures of detention fail to address the underlying problem, but further perpetuate deviant identities, leading to a “self-fulfilling prophecy” (Merton, 1968)

Discussion Using Theoretical Frameworks

Lemert’s and Becker’s Labelling Tradition

Applying Lemert’s (1951; 1967) Labelling Tradition suggests that societal reaction to minor acts of deviance can drive individuals to exhibit serious behaviours that are consistent with the associated label. Skaggs (2024) asserts, citing Becker (1963), that the sequence from “primary” deviance, where the initial unnoticed and minor acts are labelled as deviant by society. As a result, the internalisation of the status by the individual would eventually accept this label as part of their identity, compelling them to adopt these behaviours more consistently, thus transitioning into “secondary” deviance.

Jeremy’s initial label of a “latecomer” soon solidified into a more damaging label of “truant”. Jeremy’s inability to conform to the school norms led to a negative reaction from both his peers and teacher. His classmates would often remark, “Wah, bro finally show up?” or “Eh not late today?”, indicating a deeper societal rejection, pushing him further into the role his classmates gave him, despite making efforts to avoid tardiness.

As Jeremy’s labels transition, it reinforces his deviant identity, making it even more difficult for him to break the cycle and return to a conformist path – an observation of Durkheim on the functions of deviance in society (Thorlindsson, & Bernburg, 2004). Society used its power to label Jeremy, which acted as a barriers, cutting him off from resources that could help him to reintegrate him back to the legitimate school environment, the classroom, instead of the illegitimate – the detention room.

Merton’s Strain Theory

Merton’s Strain Theory (1957; 1968) provides a framework to further understand Jeremy’s “truancy” as a coping mechanism and adaptation to the socially accepted goal. According to a study done by Curci and Greco (2016), those who exhibit negative emotions such as stress or anger, are more likely to participate in deviant behaviours.

The emotional distress from his situation triggered his adaptation responses. It is important to also note that before committing the deviant act, Jeremy acknowledges that he needs to succeed academically to ensure he meets the societal expectations for material success. However, his father’s unexpected illness created an economic strain that conflicted with his academic goals at that time. According to Merton’s theory, his workaround and “truancy” can be classified as an innovative adaptation where his unconventional means to earn extra money conflicted with institutional norms

Cohen’s Subculture Theory

Cohen’s Subculture Theory (1955) plays a part in Jeremy’s transition from primary to secondary deviance. Cohen (1955) states that subculture – which refers to a group rejected by society, having shared norms and values – arises in response to similar strains experienced by individuals.

Phrases like, “come to school late also get detention, might as well don’t come” , “no point also la, the teachers don’t care about us” and “never mind, join us can already” reflects a shared norm within this subculture of frequent detainees that normalises deviant behaviour. While detention is used to maintain social order in school, these exclusionary practices can eventually lead to undesirable labels, and alienation, and could encourage them to engage in secondary deviant roles (Gerlinger et al., 2021).

Desistance from Deviance

Jeremy’s desistance from deviance can be explored through Hirschi’s (1969) Social Bond Theory. Kotlaja and Meier (2018), cited Hirschi (1969), mentioned that bonds such as family or community can deter deviant behaviours. In the interview, Jeremy mentioned that his father’s health deteriorated quickly and unfortunately passed away four months later.

These social breaks occurred once he realigned his behaviours to ensure that he could provide support for his family through proper education, and as a result, started attending school regularly and is now pursuing an undergraduate degree in a local university in Singapore. His personal loss and familial responsibility align closely with Hirschi’s theory which emphasises the importance of social ties and deterring deviance.

Conclusion

Well, the 10-year Compulsory Education Act has set an expectation for educational attainment, and would be considered deviant if one fails to comply. However, Jeremy’s journey through primary and secondary deviance illuminates the complexities of societal labelling and pressures. His experiences highlight the need to support reintegration over unproportionate measures, to foster a healthier school environment for all students.